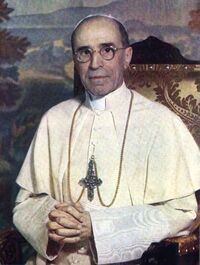

- English name - Pius XII

Pope Pius XII

- Birth name - Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli

- Term start - March 2 1939

- Term end - October 9 1958

- Predecessor - Pius XI

- Successor John XXIII

- Birth date March 2 1876

- Birth place - Rome, Italy

- Dead

- Death date - October 9 1958

- Death place - Castel Gandolfo, Italy

| Papal styles of Pope Pius XII | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | Venerable |

Pope Pius XII (Latin: Pius PP. XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (March 2, 1876 – October 9, 1958), reigned as the 260th pope, the head of the Roman Catholic Church, and sovereign of Vatican City State from March 2, 1939 until his death. His leadership of the Catholic Church during World War II and the Holocaust remains the subject of continued historical controversy. Before election to the papacy, Pacelli served as secretary of the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, papal nuncio and cardinal secretary of state, in which roles he worked to conclude treaties with European nations, most notably the Reichskonkordat with Germany. After World War II, he was a vocal supporter of lenient policies toward vanquished nations, including amnesty for war criminals. He also was a staunch opponent of communism.

Pius is one of few popes in recent history to exercise his papal infallibility by issuing an apostolic constitution, Munificentissimus Deus, which defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Assumption of Mary. He also promulgated forty-six encyclicals, including Humani Generis, which is still relevant to the Church's position on evolution. He also decisively eliminated the Italian majority in the College of Cardinals with the Great Consistory. Most sedevacantists regard Pope Pius XII as the last true Pope to occupy the Holy See. His ongoing canonization process progressed to the venerable stage on September 2, 2000 under Pope John Paul II.

Early life[]

- Main article: Early life of Pope Pius XII

Pacelli was born in Rome on March 2 1876 into a well-off aristocratic family with a history of ties to the papacy (the "Black Nobility"). His grandfather, Marcantonio Pacelli was Uder-Secretary in the Papal Ministry of Finances[1] and then Secretary of the Interior under Pope Pius IX from 1851 to 1870 and founded the Vatican's newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano in 1861;[2] his cousin, Ernesto Pacelli, was a key financial advisor to Pope Leo XII; his father, Filippo Pacelli, was the dean of the Sacra Rota Romana; and his brother, Francesco Pacelli, became a highly-regarded lay canon lawyer, credited for his role in negotiating the Lateran treaties in 1929, bringing an end to the Roman Question, whom Pius XII would later name a marchese.[3] At the age of twelve Pacelli announced his intentions to enter the priesthood instead of becoming a lawyer. Most of what is known about Pacelli's early life comes from a comprehensive biography by Sister Margherita Marchione. [4]

After completing state primary schools, Pacelli received his secondary, classical education at the Visconti Institute. In 1894, at the age of eighteen, he entered the Almo Capranica Seminary to begin study for the priesthood and enrolled at the Pontifical Gregorian University and the Appolinare Institute of Lateran University. From 1895-1896, he studied philosophy at University of Rome La Sapienza. In 1899 he received degrees in theology and in utroque jure (civil and canon law). At the seminary, he received a special dispensation to live at home for health reasons.

Church career[]

Priest and Monsignor[]

He was ordained a priest on Easter Sunday, April 2 1899 by Bishop Francesco Paolo Cassetta—the vice-regent of Rome and a family friend—and received his first assignment as a curate at Chiesa Nuova, where he had served as an altar boy. In 1901, he entered the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, a sub-office of the Vatican Secretariat of State, where he became a minutante, at the recommendation of Cardinal Vannutelli, another family friend.

In 1904, Pacelli became a papal chamberlain and in 1905 a domestic prelate. From 1904 until 1916, Father Pacelli assisted Cardinal Gasparri in his codification of canon law with the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs. He was also chosen by Pope Leo XIII to deliver condolences on behalf of the Vatican to Edward VII of the United Kingdom after the death of Queen Victoria. In 1908, he served as a Vatican representative on the International Eucharistic Congress in London, where he met with Winston Churchill. In 1910, he represented the Holy See at the coronation of King George V.

In 1908 and 1911, Pacelli turned down professorships in canon law at a Roman university and The Catholic University of America, respectively. Pacelli became the under-secretary in 1911, adjunct-secretary in 1912 (a position he received under Pope Pius X and retained under Pope Benedict XV) and secretary of the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs in 1914—succeeding Gasparri, who was promoted to Cardinal Secretary of State. As secretary, Pacelli concluded a concordat with Serbia four days before Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo. During World War I, Pacelli maintained the Vatican's registry of prisoners of war. In 1915, he travelled to Vienna to assist Monsignor Scapinelli—the apostolic nuncio to Vienna—in his negotiations with Franz Joseph I of Austria regarding Italy.

Archbishop and Papal nuncio[]

Pope Benedict XV appointed Pacelli as papal nuncio to Bavaria effective April 1917, consecrating him as a bishop in the Sistine Chapel and immediately elevating him to be archbishop of Sardis on May 13, 1917, before he left for Bavaria, where he would meet with King Ludwig III on May 28, and later with Kaiser Wilhelm II. As there was no nuncio to Prussia at the time, Pacelli was, for all practical purposes, the nuncio to all of the German Empire, having his nunciature extended to Germany and Prussia officially in June 23, 1920 and 1925 respectively. Many of Pacelli's Munich staff would stay with him for the rest of his life, including Sister Pasqualina Lehnert—housekeeper, friend, and adviser to Pacelli for 41 years.

When Eugen Levine and Kurt Eisner established a short-lived Soviet Republic in Bavaria on November 7, 1918, Pacelli was one of the few foreign diplomats to remain in Munich. In 1919, Pacelli faced down a small group of Spartacist revolutionaries and reportedly convinced them to leave the offices of the nunciature without incident. The oft-repeated anecdote—reminiscent of Pope Leo I turning Attila the Hun away from the gates of Rome—is often cited as a formative experience which informed Pacelli's later impressions of Communism and leftist movements in general.[5] Similarly, he later dispersed a mob attacking his car by raising his cross and blessing his assailants, as related by Bishop Fulton Sheen—the recipient of the cross—on television.[6]

On the night of the Beer Hall Putsch, Franz Matt, the only member of the German cabinet not present at the Bürgerbräu Keller, was having dinner with Pacelli and Michael Cardinal von Faulhaber.

During the 1920s, Pacelli succeeded in negotiating concordats with Latvia (1922), Bavaria (1925)[7], Poland (1925), Romania (1927), and Prussia (1929), but failed in regard to Germany. Under his tenure the nunciature was moved to Berlin, where one of his associates was the German priest Ludwig Kaas, who was known for his expertise in Church-state relations and was politically active in the Centre Party.[8]

Cardinal Secretary of State and Camerlengo[]

Pacelli was made a cardinal on 16 December, 1929 by Pope Pius XI. Within a few months, on 7 February 1930, Pius XI appointed Pacelli Cardinal Secretary of State. In 1935, Cardinal Pacelli was named Camerlengo of the Roman Church.

As Cardinal Secretary of State, Pacelli signed concordats with many non-Communist states in an attempt to gain recognition for the four-year-old Vatican State, including concordats with Baden (1932), Austria (1933), Germany (1933), Yugoslavia (1935) and Portugal (1940). The Lateran treaties with Italy (1929) were concluded before Pacelli rose to the office of Secretariat. Such concordats allowed the Catholic Church to organize youth groups, make ecclesiastical appointments, run schools, hospitals, and charities, or even conduct religious services. They also ensured that canon law would be recognized within some spheres (e.g. church decrees of nullity in the area of marriage).

He also made many diplomatic visits throughout Europe and the Americas, including an extensive visit to the United States in 1936 where he met with Charles Coughlin and Franklin D. Roosevelt, who appointed a personal envoy—who did not require Senate confirmation—to the Holy See in December 1939, re-establishing a diplomatic tradition that had been broken since 1870 when the pope lost temporal power.

Pacelli presided as Papal Legate over the International Eucharistic Congress in Buenos Aires, Argentina on October 10-14, 1934, and in Budapest on May 25-30, 1938.

Historians have argued that Pacelli, as Cardinal Secretary of State, dissuaded Pope Pius XI—who was nearing death at the time[9]—from condemning Kristallnacht in November 1938,[10] when he was informed of it by the papal nuncio in Berlin. [11]

Reichskonkordat[]

- Main article: Reichskonkordat

The Reichskonkordat, signed on July 20, 1933, between Germany and the Holy See remains the most important and controversial of Pacelli's concordats. A national concordat with Germany was one of Pacelli's main objectives as secretary of state. As nuncio during the 1920s he had made unsuccessful attempts to obtain German agreement for such a treaty, and between 1930 and 1933 he attempted to initiate negotiations with representatives of successive German governments.[12][13]

Heinrich Brüning, leader of the Catholic German Centre Party and Chancellor of Germany met with Pacelli on August 8, 1931. According to Brüning's memoirs Pacelli suggested that he disband the Centre Party's governing coalition with the Social Democrats and "form a government of the right simply for the sake of a Reich concordat, and in doing so make it a condition that a concordat be concluded immediately." Brüning refused to do so, replying that Pacelli "mistook the political situation in Germany and, above all, the true character of the Nazis."[14]

Between 1933 to 1939, Pacelli would issue 55 protests of violations of the Reichskonkordat. Most notably, early in 1937, Pacelli asked several German cardinals, including Michael Cardinal von Faulhaber to help him write a protest of Nazi violations of the Reichskonkordat, which would become Pius XI's encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge. The encyclical, condemning racism and statism, was written in German instead of Latin and read in German churches on Palm Sunday 1937.[15].

Papacy[]

Election and Coronation[]

- Main article: Papal conclave, 1939

Pope Pius' Coat of Arms featured a dove, a symbol of diplomacy

Pope Pius XI died on 10 February, 1939. Several historians have interpreted the conclave to choose his successor as facing a choice between a diplomatic or spiritual candidate, and they view Pacelli's diplomatic experience, especially with Germany, as one of the deciding factors in his election on 2 March 1939, his 63rd birthday, after only one day of deliberation and three ballots.[16][17] Pacelli took the name of Pius XII, the same papal name as his predecessor, a title used exclusively by Italian Popes. He was the first cardinal secretary of state to be elected Pope since Clement IX in 1667.[18] He was also one of only two men known to have served as camerlengo immediately prior to being elected as pope (the other being Gioacchino Cardinal Pecci, who was elected as Pope Leo XIII).

After the election, German media complained about the "prejudiced hostility and incurable lack of comprehension" shown by the Holy See. The morning after Pius XII's election, the Berlin Morgenpost reported: "The election of Cardinal Pacelli is not accepted with favor in Germany because he was always opposed to National Socialism and practically determined the policies of the Vatican under his predecessor." Das Schwarze Korps, the official publication of the SS, said: "As nuncio and secretary of state, Eugenio Pacelli had little understanding of us; little hope is placed in him. We do not believe that as Pius XII he will follow a different path."

Theology[]

Pope Pius XII accepted the Rhythm Method as a moral form of family planning, although only in limited circumstances, in two speeches on October 29, 1951, and November 26, 1951. (These speeches were translated into English and published under the title Moral Questions Affecting Married Life.) Some had controversially interpreted Pope Pius XI's 1930 encyclical Casti Connubii to allow moral use of Rhythm, but these speeches by Pope Pius XII were the first explicit acceptance of any method of birth regulation aside from complete sexual abstinence. The Catholic Church's modern view on family planning was further developed in the 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae by Pope Paul VI.

Pius was an energetic proponent of the theory of the Big Bang. As he told the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1951: "...it would seem that present-day science, with one sweep back across the centuries, has succeeded in bearing witness to the august instant of the primordial Fiat Lux [Let there be Light], when along with matter, there burst forth from nothing a sea of light and radiation, and the elements split and churned and formed into millions of galaxies."[19]

Apostolic Constitutions[]

Pius is one of few popes in recent history to exercise his Papal Infallibility by issuing, on November 1 1950 an apostolic constitution, Munificentissimus Deus, which defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven. He consecrated the world to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1942, in accordance with the second "secret" of Our Lady of Fatima.

His other apostolic constitutions are Sponsa Christi (November 21, 1950), Bis Saeculari Die (September 27, 1948), and Provida Mater Ecclesia (February 2, 1947).

Encyclicals[]

- Main article: Encyclicals of Pope Pius XII

Summi Pontificatus, Pius's first encyclical, promulgated in 1939 condemned the "ever-increasing host of Christ's enemies."

Humani Generis, promulgated in 1950, acknowledged that evolution might accurately describe the biological origins of human life, but at the same time criticized those who "imprudently and indiscreetly hold that evolution... explains the origin of all things". The encyclical reiterated the Church's teaching that, whatever the physical origins of human beings, the human soul was directly created by God.[20] While Humani Generis was significant as the first occasion on which a pope explicitly addressed the topic of evolution at length, it did not represent a change in doctrine for the Catholic Church. As early as 1868, Cardinal John Henry Newman wrote, "the theory of Darwin, true or not, is not necessarily atheistic; on the contrary, it may simply be suggesting a larger idea of divine providence and skill."[21]

Pope John Paul II went further in acknowledging the success of evolutionary theory in his 1996 Message to Pontifical Academy of Sciences. He called evolution "more than a hypothesis" and said, "It is indeed remarkable that this theory has been progressively accepted by researchers, following a series of discoveries in various fields of knowledge."

Divino Afflante Spiritu, published in 1953, encouraged Christian theologians to revisit original versions of the Bible in Greek and Latin. Noting improvements in archaeology, the encyclical reversed Pope Leo XIII's Providentissimus Deus (1893), which had only advocated going back to the original texts to resolve ambiguity in the Latin Vulgate.[22]

Canonizations and Beatifications[]

During his reign, Pius XII canonized thirty-four saints, including Gemma Galgani, Mother Cabrini, Catherine Labouré, John de Britto, Joseph Cafasso, Saint Louis de Montfort, Nicholas of Flue, Joan of France, Duchess of Berry, Maria Goretti, Dominic Savio[23], Pope Pius X, and Peter Chanel. He beatified six people. He named Saint Casimir the patron saint of all youth.

Great Consistory[]

Only twice in his pontificate did Pius XII hold a consistory to create new cardinals, in contrast to Pius XI, who had done so seventeen times in seventeen years. The first occasion has been known as the "Great Consistory", of February 1946; it was the largest in the history of the Church up to that time, and brought an end to over five hundred years of Italians constituting a majority of the College. By his appointments then and in 1953 he substantially reduced the proportion of cardinals who belonged to the Roman Curia.

Earlier in 1945 Pius XII had dispensed with the complicated papal conclave procedures which attempted to ensure secrecy while preventing Cardinals from voting for themselves, compensating for this change by raising the requisite majority from two-thirds to two thirds plus one.

World War II[]

Pius XII's pontificate began on the eve of the Second World War. During the war, the Pope followed a policy of neutrality mirroring that of Pope Benedict XV during the First World War.

In April 1939, after the submission of Charles Maurras and the intervention of the Carmel of Lisieux, Pius XII ended his predecessor's ban on Action Française, a virulently anti-Semitic and anti-Communist organization.[24][25] The Pope employed Professor Almagia in 1939 to work on old maps in the Vatican library. On January 25, 1940, Pius received Almagia in private audience and thanked him in writing for "his splendid work. The Pope's appointment of two Jews to the Vatican Academy of Science as well as the hiring of Almagia were reported by the New York Times in the editions of November 11, 1939, and January 10, 1940.[26]

On 18 January 1940, after over 15,000 Polish civilians had been killed, Pius XII said in a radio broadcast, "The horror and inexcusable excesses committed on a helpless and a homeless people have been established by the unimpeachable testimony of eye-witnesses."[27]

After Germany invaded the Benelux during 1940, Pius XII sent expressions of sympathy to the Queen of the Netherlands, the King of Belgium, and the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg. When Mussolini learned of the warnings and the telegrams of sympathy, he took them as a personal affront and had his ambassador to the Vatican file an official protest, charging that Pius XII had taken sides against Italy's ally Germany. In any case, Mussolini's foreign minister claimed that Pius XII was "ready to let himself be deported to a concentration camp, rather than do anything against his conscience."[28].

In the spring of 1940, a group of German generals seeking to overthrow Hitler and make peace with the English approached Pope Pius XII, who acted as a negotiator between the British and the abortive plot.[29]

In April 1941 Pius XII granted a private audience to Ante Pavelić, the leader of the newly proclaimed Croatian state (rather than the diplomatic audience Pavelić had wanted).[30] Pius was criticised for his reception of Pavelić: an unattributed British Foreign Office memo on the subject described Pius as "the greatest moral coward of our age".[31] The Vatican did not officially recognise Pavelić's regime. Pius XII did not publicly condemn the expulsions and forced conversions to Catholicism perpetrated on Serbs by Pavelić[32]; however, the Holy See did expressly repudiate the forced conversions in a memorandum dated January 25, 1942, from the Vatican Secretiat of State to the Yugoslavian Legation.[33]

In 1941, Pius XII interpreted Divini Redemptoris, an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, which forbade Catholics to help Communists, as not applying to military assistance to the Soviet Union. This interpretation assuaged American Catholics who had previously opposed Lend-Lease arrangements with the Soviet Union.[34]

In March 1942, Pius XII established diplomatic relations with the Japanese Empire. In May 1942, Kazimierz Papée, Polish ambassador to the Vatican, complained that Pius had failed to condemn the recent wave of atrocities in Poland; when Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione replied that the Vatican could not document individual atrocities, Papée declared, "when something becomes notorious, proof is not required."[35]

Pius XII's famous Christmas broadcast on the Vatican Radio delivered December 24, 1942—which at 26 pages and over 5000 words took more than 45 minutes to deliver—remains a "lightning rod" in debates about Pope Pius XII during the war, particularly the Holocaust.[36] The majority of the speech spoke generally about human rights and civil society; at the very end of the speech, Pius seems to turn to current events, albeit not specifically, referring to "all who during the war have lost their Fatherland and who, although personally blameless, have simply on account of their nationality and origin, been killed or reduced to utter destitution."[37]

As the war was approaching its end in 1945, Pius advocated a lenient policy by the Allied leaders in an effort to prevent what he perceived to be the mistakes made at the end of World War I.

The Holocaust[]

- Main article: The Holocaust

Pius engineered an agreement—formally approved on June 23, 1939—with Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas to issue 3,000 visas to "non-Aryan Catholics". However, over the next eighteen months Brazil’s Conselho de Imigração e Colonização (CIC) continued to tighten the restrictions on their issuance—including requiring a baptismal certificate issued dated before 1933, a substantial monetary transfer to the Banco de Brasil, and approval by the Brazilian Propaganda Office in Berlin—culminating in the cancellation of the program fourteen months later, after fewer than 1,000 visas had been issued, amid suspicions of "improper conduct" (i.e. continuing to practice Judaism) among those who had received visas.[38][11]

In the spring of 1940, Chief Rabbi of Palestine, Isaac Herzog, asked Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Maglione to intercede on behalf of Lithuanian Jews facing deportation to Germany.[11] Pius called Ribbentrop on March 11, repeatedly protesting against the treatment of Jews.[39]

In 1941 Cardinal Theodor Innitzer of Vienna informed Pius of Jewish deportations in Vienna.[37] Later that year, when asked by French Marshal Philippe Pétain if the Vatican objected to anti-Jewish laws, Pius responded that the church condemned anti-semitism, but would not comment on specific rules.[37] Similarly, when Pétain's puppet government adopted the "Jewish statutes," the Vichy ambassador to the Vatican, Léon Bérard, was told that the legislation did not conflict with Catholic teachings.[40] Valerio Valeri, the nuncio to France was "embarrassed" when he learned of this publicly from Pétain[41] and personally checked the information with Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione[42] who confirmed the Vatican's position.[43] In September 1941 Pius objected to a Slovakian Jewish Code[44], which, unlike the earlier Vichy codes, prohibited intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews.[45] In October 1941 Harold Tittman, a U.S. delegate to the Vatican, asked the pope to condemn the atrocities against Jews; Pius replied that the Vatican wished to remain "neutral,"[46] reiterating the neutrality policy which Pius invoked as early as September 1940.[47]

In 1942, the Slovakian charge d'affaires, told Pius that Slovakian Jews were being sent to concentration camps.[37] On March 11, 1942, several days before the first transport was due to leave, the papal nuncio in Bratislava reported to the Vatican: "I have been assured that this atrocious plan is the handwork of.....Prime Minister (Tuka), who confirmed the plan... he dared to tell me - he who makes such a show of his Catholicism - that he saw nothing inhuman or un-christian in it...the deportation of 80,000 persons to Poland, is equivalent to condemning a great number of them to certain death." The Vatican protested to the Slovak government that it "deplore(s) these...measures which gravely hurt the natural human rights of persons, merely because of their race."[48]

In August 1942, by which time it has been estimated that thousands of Ukrainian Jews had been killed in the eastern front, in response to a letter from Andrej Septyckyj, Pius advised Septyckyj to "bear adversity with serene patience" (a quote from Psalms).[49] On 18 September 1942, Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini (who would later become Pope Paul VI), wrote to Pius, "the massacres of the Jews reach frightening proportions and forms."[37] Later that month, when Myron Taylor, U.S. representative to the Vatican, warned Pius that silence on the atrocities would hurt the Vatican's "moral prestige"—a warning which was echoed simultaneously by representatives from Great Britain, Brazil, Uruguay, Belgium, and Poland[50]— the Cardinal Secretary of State replied that the rumors about genocide could not be verified.[51] In December 1942, when Tittman asked Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione if Pius would issue a proclamation similar to the Allied declaration "German Policy of Extermination of the Jewish Race," Maglione replied that the Vatican was "unable to denounce publicly particular atrocities."[52]

In late 1942 Pius XII advised German and Hungarian bishops that speaking out against the massacres in the eastern front would be politically advantageous.[53] On April 7, 1943, Cardinal Tardini, one of Pius’s closest advisors, told Pius that it would be politically advantageous after the war to take steps to help Slovakian Jews. [54]

In January 1943, Pius would again refuse to publicly denounce the Nazi violence against Jews, following requests to do so from Wladislaw Raczkiewicz, president of the Polish government-in-exile, and Bishop Konrad von Preysing of Berlin.[55] On September 26, 1943, following the german occupation of northern Italy, Nazi officials gave Jewish leaders in Rome 36 hours to produce 50 kilograms of gold (or the equivalent) threatening to take 300 hostages. Then Chief Rabbi of Rome, Israel Zolli recounts in his memoir, that he was selected to go to the Vatican and seek help.[56] The Vatican offered to loan 15 kilos, but the offer proved unnecessary when the Jews received an extension.[57] Soon afterwards, when deportations from Italy were imminent, 477 Jews were hidden in the Vatican itself and another 4,238 were protected in Roman monasteries and convents.[58]

On April 30, 1943, Pius wrote to Archbishop Von Preysing of Berlin to say : "We give to the pastors who are working on the local level the duty of determining if and to what degree the danger of reprisals and of various forms of oppression occasioned by episcopal declarations...seem to advise caution....The Holy See has done whatever was in its power, with charitable, financial and moral assistance. To say nothing of the substantial sums which we spent in American money for the fares of immigrants.".[59]

On October 28 1943, Weizsacker, the German Ambassador to the Vatican, telegrammed Berlin that the pope "has not allowed himself to be carried away [into] making any demonstrative statements against the deportation of the Jews." [60]

In March 1944, through the papal nuncio in Budapest, Angelo Rotta urged the Hungarian government to moderate its treatment of the Jews.[61] These protests, along with others from the King of Sweden, the International Red Cross, the United States, and Britain led to the cessation of deportations on 8 July, 1944.[62] Also in 1944, Pius appealed to 13 Latin American governments to accept "emergency passports", although it also took the intervention of the U.S. State Department for those countries to honor the documents.[63]

When the church transferred 6,000 Jewish children in Bulgaria to Palestine, Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione reiterated that the Holy See was not a supporter of Zionism.[61]

On September 21, 1945, the general secretary of the World Jewish Council, Dr. Leon Kubowitzky, presented an amount of money to the pope, "in recognition of the work of the Holy See in rescuing Jews from Fascist and Nazi persecutions."[64]

After the war, in the autumn of 1945, Harry Greenstein from Baltimore, a close friend of Chief Rabbi Herzog of Jerusalem, told Pius how grateful Jews were for all he had done for them. "My only regret," the pope replied, "is not to have been able to save a greater number of Jews."[65]

Post-World War II[]

After the war, Israel Zolli, the Chief Rabbi of Rome, converted to Catholicism, taking the baptismal name Eugenio, in honor of Pius.

Pius's anti-Communist activities became more potent following the war. In 1948, Pius declared that any Italian Catholic who supported Communist candidates in the parliamentary elections of that year would be excommunicated and also encouraged Azione Cattolica to support the Italian Christian Democratic Party. In 1949, he authorized the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to excommunicate any Catholic who joined or collaborated with the Communist Party. He also publicly condemned the Soviet crackdown on the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.[66]

After the war, Pius also became an outspoken advocate of clemency and forgiveness for all, including war criminals. He also applied pressure through his U.S. nuncio to commute the sentences of Germans convicted by the occupation authorities. The Vatican also asked for a blanket pardon for all those who had received death sentences, after the ban on execution of war criminals was lifted in 1948.[67]

Pius concluded concordats with Francisco Franco's Spain in 1953 and Rafael Trujillo's Dominican Republic in 1954. In both countries, the rights of the Catholic Church had been violated by repressive regimes. Pius would also excommunicate Juan Perón in 1955 for his arrests of church officials.[68]

Jewish orphans controversy[]

In 2005, Corriere della Sera published a document dated 20 November, 1946, ordering that Jewish children in France who had been baptized by Catholics during the war should be kept in the custody of the Church; the document stated that the decision "has been approved by the Holy Father." Angelo Roncalli (who would become Pope John XXIII) ignored this directive.[69] Two Italian scholars, Matteo Luigi Napolitano and Andrea Tornielli, confirmed that the memorandum was genuine although the initial reporting by the Coriere della Sera was misleading, as the document had originated in the French Catholic Church archives rather than the Vatican archives.[70] Abe Foxman, the national director of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), called for an immediate freeze on Pius's beatification process until the relevant Vatican Secret Archives and baptismal records were opened. Foxman, a Holocaust survivor who was baptized by his Polish Catholic nanny during the war, had undergone a similar protracted custody battle after the war.[71]

Later life, death, and legacy[]

Pius was dogged with ill health later in life, largely due to a charlatan, Riccardo Galeazzi-Lisi, whom Pius made an honorary member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Pius suffered from gastritis brought on by kidney dysfunctions. Galeazzi-Lisi, with the aid of a Swiss colleague, prescribed injections made from the glands of fetal lambs that gave Pius chronic hiccups and rotting teeth.[72][73]

The role of Sister Pasqualina Lehnert—who had served Pacelli since he was nuncio to Bavaria—also became controversial as Pius fell under ill-health. Many—including Pius's family members who called her scaltrissima (Italian for "very cunning") and asked Pius to dismiss her from the Prefecture for the Pontifical Household—distrusted the level of influence she allegedly had, including controlling access to the ailing pope. Most notably, many in the curia speculated that she convinced Pius to deny a cardinalate to Archbishop Giovanni Montini (who later became Pope Paul VI), thus making him ineligible for the 1958 papal conclave.[74] Montini was the first person appointed cardinal by Pope John XXIII, Pius's eventual successor.

Pius died on October 9, 1958 in Castel Gandolfo, the papal summer residence. Galeazzi-Lisi gained admittance as the pope lay dying and took photographs of Pius which he tried unsuccessfully to sell to some magazines, forcing him to resign as head of the Vatican medical services in the wake of massive public protests.

When Pius died, Galeazzi-Lisi assumed the role of Pius' embalmer. Rather than slow the process of decay, the doctor-mortician's self-made technique (aromatizazzione), which involved encasing Pius in a cellophane bag with herbs and spices, sped it up, causing the Holy Father's corpse to disintegrate rapidly, turning purple; at one point, the nose's remains fell off. It is reported that while transporting the pope's body from Castel Gandolfo to the Vatican, pressure within the coffin due to gases given off by decay blew off the seals.[72] The stench caused by the decay was such that guards had to be rotated every 15 minutes, otherwise they would collapse. The condition of the body became so bad that the remains were secretly removed at one point for further treatments before being returned in the morning. This caused considerable embarrassment to the Vatican and one of the first acts of Pius' successor, Pope John XXIII, was to ban the charlatan from Vatican City for life.[75]

The Italian Medical Council expelled Galeazzi-Lisi for "infamous conduct" but the High Court of the Italian Central Health Commission reversed the decision.[76]

On September 2, 2000. during the pontificate of Pope John Paul II, Pius's cause for canonization was elevated to the level of Venerable. Rome's Chief Rabbi Elio Toaff also began promoting the cause of Pius to receive such posthumous recognition from Yad Vashem as a "righteous gentile". The Boy Scouts of America named the highest Catholic Award after him.

Views, interpretations, and scholarship[]

Contemporary[]

During the war, the pope was widely praised for making a principled stand. For example, Time Magazine credited Pius XII and the Catholic Church for "fighting totalitarianism more knowingly, devoutly, and authoritatively, and for a longer time, than any other organized power"[77] Some early works echoed these favorable sentiments, including Oskar Halecki's Pius XII: Eugenio Pacelli: Pope of peace (1954) and Nazareno Padellaro's Portrait of Pius XII (1949).

Many Jews publicly thanked the pope for his help. For example, Pinchas Lapide, a Jewish theologian and Israeli diplomat to Milan in the 1960s, estimated that Pius "was instrumental in saving at least 700,000 but probably as many as 860,000 Jews from certain death at Nazi hands." Some historians have questioned these figures. Dr. Raffael Cantoni, head of the Italian Jewish community’s wartime Jewish Assistance Committee, stated that "six million of my coreligionists have been murdered by the Nazis, but there could have been many more victims had it not been for the efficacious intervention of Pius XII." Moshe Sharett, later Israel’s second Prime Minister, met with Pius in the closing stages of the war and said, "I told [him] that my first duty was to thank him, and through him the Catholic Church, on behalf of the Jewish public for all they had done in the various countries to rescue Jews. . . . We are deeply grateful to the Catholic Church." Golda Meir, Israel’s Foreign Minister, eulogized that "when fearful martyrdom came to our people in the decade of Nazi terror, the voice of the Pope was raised for the victims."

Kevin Madigan interprets this and other praise from prominent Jewish leaders, including Golda Meir, as less than sincere, an attempt to secure Vatican recognition of the State of Israel.[78]

Pius was also criticized during his lifetime. For example, Leon Poliakov wrote five years after World War II that Pius had been a tacit supporter of Vichy France's anti-Semitic laws, calling him "less forthright" than Pope Pius XI either out of "Germanophilia" or the hope that Hitler would defeat communist Russia.[79]

The Deputy[]

- Main article: The Deputy

In 1963, Rolf Hochhuth's controversial drama Der Stellvertreter. Ein christliches Trauerspiel (The Deputy, a Christian tragedy, released in English in 1964) portrayed Pope Pius XII as a hypocrite who remained silent about the Holocaust. Books such as Dr. Joseph Lichten's A Question of Judgment (1963), written in response to The Deputy, defended Pius XII's actions during the war. Lichten labelled any criticism of the pope's actions during World War II as "a stupefying paradox" and said, "no one who reads the record of Pius XII's actions on behalf of Jews can subscribe to Hochhuth's accusation." Critical scholarly works like Guenther Lewy's The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany (1964) also followed the publication of The Deputy.

Actes[]

- Main article: Actes et Documents du Saint Siège relatifs à la Seconde Guerre Mondiale

In the aftermath of the controversy surrounding The Deputy, in 1964 Pope Paul VI authorized four Jesuit scholars to access the Vatican's secret archives, which are normally not opened for seventy-five years. A selected collection of primary sources, Actes et Documents du Saint Siège relatifs à la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, was published in eleven volumes between 1965 and 1981. The Actes documents are not translated from their original language (mostly Italian) and the volume introductions are in French. Only one volume has been translated into English.

Notable documents not included in the Actes include most of the letters from Bishop Konrad Preysing of Berlin to Pope Pius XII in 1943 and 1944, the papers of Austrian bishop Alois Hudal, and virtually everything appertaining to Eastern Europe.[80] Saul Friedlander's Pope Pius and the Third Reich: A Documentation (1966) did not cite the Actes and drew instead on unpublished diplomatic documents from German embassies. Most later historical works, however, draw heavily on the Actes.

Hitler's Pope[]

- Main article: Hitler's Pope

In 1999, John Cornwell's Hitler's Pope criticized Pius for not doing enough, or speaking out enough, against the Holocaust. Cornwell argues that Pius's entire career as the nuncio to Germany, cardinal secretary of state, and pope was characterized by a desire to increase and centralize the power of the Papacy, and that he subordinated opposition to the Nazis to that goal. He further argues that Pius was anti-Semitic and that this stance prevented him from caring about the European Jews.

Cornwell's work was the first to have access to testimonies from Pius's beatification process as well as to many documents from Pacelli's nunciature which had just been opened under the seventy-five year rule by the Vatican State Secretary archives.[81] Cornwell concluded, "Pacelli's failure to respond to the enormity of the Holocaust was more than a personal failure, it was a failure of the papal office itself and the prevailing culture of Catholicism."

Cornwell's work has received much praise and criticism. Much praise of Cornwell centered around his admission that he was a practising Catholic who had attempted to absolve Pius with his work.[82] Works such as Susan Zuccotti's Under His Very Windows: The Vatican and the Holocaust in Italy (2000) and Michael Phayer's The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 (2000) are critical of both Cornwell and Pius.

Cornwell's scholarship has been criticized. For example, Kenneth L. Woodward stated in his review in Newsweek that "errors of fact and ignorance of context appear on almost every page."[83] Cornwell himself gives a more ambiguous assessment of Pius' conduct in a 2004 interview where he states that "Pius XII had so little scope of action that it is impossible to judge the motives for his silence during the war"[84] Most recently, Rabbi David Dalin's The Myth of Hitler's Pope argues that critics of Pius are liberal Catholics who "exploit the tragedy of the Jewish people during the Holocaust to foster their own political agenda of forcing changes on the Catholic Church today" and that Pius XII was actually responsible for saving the lives of thousands of Jews.[85]

ICJHC[]

- Main article: International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission

In 1999, in an attempt to address some of this controversy, the Vatican appointed the International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission (ICJHC), a group composed of three Jewish and three Catholic scholars to investigate the role of the Church during the Holocaust. In 2001, the ICJHC issued its preliminary finding, raising a number of questions about the way the Vatican dealt with the Holocaust, titled " The Vatican and the Holocaust: A Preliminary Report."

The Commission discovered documents making it clear that Pius was aware of widespread anti-Jewish persecution in 1941 and 1942, and they suspected that the Church may have been influenced in not helping Jewish immigration by the nuncio of Chile and the Papal representative to Bolivia, who complained about the "invasion of the Jews" to their countries, where they engaged in "dishonest dealings, violence, immorality, and even disrespect for religion." (Questions 7 and 12 of the ICJHC report)

The ICJHC raised a list of 47 questions about the way the Church dealt with the Holocaust, requested documents that had not been publicly released in order to continue their work, and, not receiving permission, they disbanded in July of 2001, having never issued a final report. Unsatisfied with the findings, Dr. Michael Marrus, one of the three Jewish members of the Commission, said the commission "ran up against a brick wall.... It would have been really helpful to have had support from the Holy See on this issue."[86]

References[]

- Cornwell, John. (1999). Hitler's Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII. Viking. ISBN 0-670-87620-8. Also see Amazon Online Reader.

- Dalin, Rabbi David G. (2005). The Myth of Hitler's Pope: How Pope Pius XII Rescued Jews from the Nazis. Regnery. ISBN 0-89526-034-4.

- Falconi, Carlo. (1965). The Silence of Pius XII. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co. ISBN 0-571-09147-4

- Feldkamp, Michael F. Pius XII. und Deutschland. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-34026-5.

- Friedländer, Saul. (1966). Pius XII and the Third Reich: A Documentation. New York: Alfred A Knopf. ISBN 0-374-92930-0

- Gallo, Patrick J., ed. (2006). Pius XII, The Holocaust and the Revisionists. London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 0-7864-2374-9

- Gutman, Israel, ed. (1990). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, vol. 3. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-02-864529-4

- Halecki, Oskar.(1954). Pius XII: Eugenio Pacelli: Pope of peace. Farrar, Straus and Young. ASIN B0006ATVX6

- Kent, Peter. (2002). The Lonely Cold War of Pope Pius XII : The Roman Catholic Church and the Division of Europe, 1943-1950. Ithaca : McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2326-X

- Lapide, Pinchas (1980). The Last Three Popes and the Jews. London:Souvenir Press.

- Lewy, Guenter. (1964). The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-306-80931-1

- Marchione, Sr. Margherita. (2000). Pope Pius XII: Architect for Peace. Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-3912-X

- Marchione, Sr. Margherita. (2004). Man of Peace: An Abridged Life of Pope Pius XII. Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-4245-7

- McInerney, Ralph. (2001). The Defamation of Pius XII. St Augustine's Press. ISBN 1-890318-66-3

- Murphy, Paul I. and Arlington, R. Rene. (1983) La Popessa: The Controversial Biography of Sister Pasqualina, the Most Powerful Woman in Vatican History. New York: Warner Books Inc. ISBN 0-446-51258-3

- Padellaro, Nazareno. (1949). Portrait of Pius XII. Dutton; 1st American ed edition (1957). ASIN B0006AUJ2S

- Phayer, Michael. (2000). The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930-1965. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33725-9.

- Ritner, Carol and Roth, John K., eds. (2002). Pope Pius XII and the Holocaust. New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-0275-2

- Rychlak, Ronald J. (2000). Hitler, the War, and the Pope. Our Sunday Visitor. ISBN 0-87973-217-2. Also see Amazon Online Reader

- Sánchez, José M. (2002). Pius XII and the Holocaust: Understanding the Controversy. Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 0-8132-1081-X

- Scholder, Klaus. (1987). The Churches and the Third Reich. London.

- Volk, Ludwig. (1972) Das Reichskonkordat vom 20. Juli 1933. Mainz: Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag. ISBN 3-7867-0383-3.

- Zolli, Israel. (1997). Before the Dawn. Roman Catholic Books (Reprint edition). ISBN 0-912141-46-8. Also see Amazon Online Reader

- Zuccotti, Susan. (2000). Under his very Windows, The Vatican and the Holocaust in Italy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08487-0

- Roosevelt, Franklin D.; Myron C. Taylor, ed. Wartime Correspondence Between President Roosevelt and Pope Pius XII. Prefaces by Pius XII and Harry Truman. Kessinger Publishing (1947, reprinted, 2005). ISBN 1-4191-6654-9

Notes[]

- ↑ Pollard, 2005, p. 70.

- ↑ Marchione, 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ Marchione, 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ Sr. Margherita Marchione, Pope Pius XII: Architect for Peace (Paulist Press, 2000). ISBN 0-8091-3912-X

- ↑ Sanchez, 2000, p. 103-104.

- ↑ Marchione, 2002.

- ↑ Signed March 29, 1924; Ratified by Parliament on January 15, 1925

- ↑ Ludwig Volk Das Reichskonkordat vom 20. Juli 1933 ISBN 3-7867-0383-3.

- ↑ Phayer, 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ Walter Bussmann, 1969, "Pius XII an die deutshen Bischofe", Hochland 61: p. 61-65

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Gutman, Israel, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, p. 1136.

- ↑ Ludwig Volk Das Reichskonkordat vom 20. Juli 1933 ISBN 3-7867-0383-3.

- ↑ Klaus Scholder "The Churches and the Third Reich" volume 1: especially part 1 chap 10 'Concordat Policy and the Lateran Treaties (1930-33); part 2 chap 2 "The Capitulation of Catholicism" (February-March 1933)

- ↑ Heinrich Brüning Memoiren, English translation as quoted in Scholder pp.152-3

- ↑ Phayer 2000, p. 16; Sanchez 2002, p. 16-17.

- ↑ Michael F. Feldkamp Pius XII. und Deutschland ISBN 3-525-34026-5.

- ↑ Dalin, 2005, p. 69-70

- ↑ Catholic Forum. Pope Pius XII.

- ↑ The Vatican's View of Evolution: The Story of Two Popes. Doug Linder. 2004

- ↑ Humani Generis. 1950.

- ↑ [1]Catholic Online

- ↑ Divino Afflante Spiritu. 1953.

- ↑ Pius XII beatified Dominic Savio in 1950 and canonized him in 1954.

- ↑ Friedländer, Saul, 1997, Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution, New York: HarperCollins, p. 223.

- ↑ McInerny, 2001, p49.

- ↑ McInerny, 2001, p47.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin, The Second World War, p. 40.

- ↑ Dalin, David G. The Myth of Hitler's Pope: How Pope Pius XII Rescued Jews from the Nazis. Regnery Publishing. Washington, 2005. ISBN 0-89526-034-4. p. 76.

- ↑ Prof. John S. Conway: The Vatican, the Nazis and Pursuit of Justice.

- ↑ Minutes of August 7, 1941. British Public Records Office FO 371/30175 57760

- ↑ Mark Aarons and John Loftus Unholy Trinity pp.71-2

- ↑ Israel Gutman (ed.)Encyclopedia of the Holocaust vol 2 p.739

- ↑ Ronald Rychlak, Hitler, the War, and the Pope, pp414-15 n.61

- ↑ Mary Ball Martinez. 1993. "Pope Pius XII and the Second World War". Journal of Historical Review. v. 13.

- ↑ Report by the Polish Ambassador to the Holy See on the Situation in German-occupied Poland, Memorandum No. 79, May 29, 1942, Myron Taylor Papers, NARA.

- ↑ Rittner and Roth, 2002, p. 4.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Gutman, Israel, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, p. 1137.

- ↑ Lesser,Jeffrey. 1995. Welcoming the Undesirables: Brazil and the Jewish Question. University of California Press. p. 151-168.

- ↑ McInerny, 2001, p49.

- ↑ Perl, William, The Holocaust Conspiracy, p. 200.

- ↑ Phayer, 2000, p. 5.

- ↑ Michael R. Marrus and Robert O. Paxton, 1981, Vichy France and the Jews, New York: Basic Books, p. 202.

- ↑ Delpech, Les Eglises et la Persécution raciale, p. 267.

- ↑ John F. Morley, 1980, Vatican Diplomacy and the Jews during the Holocaust, 1939-1943, New York: KTAV, p. 75.

- ↑ Phayer, 2000, p.5

- ↑ Perl, William, The Holocaust Conspiracy, p. 206.

- ↑ Perl, William, The Holocaust Conspiracy, p. 200.

- ↑ Lapide, 1980, p139.

- ↑ Hilberg, Raul, Perpetrators Victims Bystanders, p. 267.

- ↑ Phayer, 2000, p. 27-28.

- ↑ Israel Pocket Library, Holocaust, p. 133; Gutman, Israel, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, p. 1137.

- ↑ Hilberg, Raul, The Destruction of the European Jews, p. 315.

- ↑ Israel Pocket Library, Holocaust, p. 136.

- ↑ Actes et documents du Saint Sie`ge relatifs a` la Seconde Guerre mondiale / e´d. par Pierre Blet, Angelo Martini, Burkhart Schneider. 7th April 1943

- ↑ Israel Pocket Library, Holocaust, p. 134.

- ↑ Eugenio Zolli. Before the Dawn. Reissued in 1997 as Why I Became a Catholic.

- ↑ Israel Pocket Library, Holocaust, p. 133.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin, The Holocaust, p. 623.

- ↑ McInerney, 1980, p 109.

- ↑ Berel Lang. "Not Enough" vs. "Plenty": Which did Pius XII do?. Judaism. Fall 2001.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Gutman, Israel, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, p. 1138.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin, The Holocaust, p. 701.

- ↑ Perl, William, The Holocaust Conspiracy, p. 176.

- ↑ McInernny, 2001, p155.

- ↑ McInernny, Ralph, The Defamation of Pius XII, 2001.

- ↑ Sanchez, 2000, p. 94-95.

- ↑ Phayer, 2002, "Ethical Questions about Papal Policy" in Pope Pius XII and the Holocaust, p. 228-229; Catholic University of America Archives, 37/133 #112.

- ↑ Torcuato Salvador Di Tella. 2003. History of Political Parties in Twentieth-Century Latin America. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0181-7. p. 77.

- ↑ Jerusalem Report, (February 7, 2005).

- ↑ Dimitri Cavalli. Pius's Children. The American. April 1, 2006.

- ↑ Anti-Defamation League. ADL to Vatican: Open Baptismal Records and Put Pius Beatification on Hold. January 13, 2005.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Heirs of the Fisherman : Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession - ISBN 0-19-517834-3

- ↑ Papal Preservation. Steven Palmer. YB News. June 2005.

- ↑ Murphy and Arlington, 1983.

- ↑ Guide to Age. Alexander Chancellor. The Guardian. April 16 2005.

- ↑ The Pope's Doctor. Alan McElwain. Annals Australia. July 1989.

- ↑ Time. August 16, 1943.

- ↑ Kevin Madigan. Judging Pius XII, page 2. Christian Century. March 14, 2001.

- ↑ Leon Poliakov. November 1950. "The Vatican and the 'Jewish Quesiton': The Record of the Hitler Period—and After." Commentary 10: 439-449.

- ↑ Michael Phayer. 2000. The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930-1965. Indiana University Press. p. xvii.

- ↑ Sanchez, 2002, p. 34.

- ↑ Sanchez, 2002.

- ↑ Kenneth L. Woodward. Newsweek. September 27, 1999.

- ↑ | For God's sake. The Economist. Dec 9th 2004.

- ↑ Dalin, 2005, p. 3.

- ↑ Melissa Radler. "Vatican Blocks Panel's Access to Holocaust Archives." The Jerusalem Post. July 24, 2001.

External links[]

- General

- Official documents

- October 2000 Report of the International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission, *notice of Commission suspending work

- Complete Text of the Concordat between the Vatican and Germany

- Pro-Pius

- The Holy See vs. the Third Reich

- Jewish Historian Praises Pius XII

- Did Pius XII Remain Silent?

- Pius XII and the Jews: The War Years, as reported by the New York Times

- Righteous Gentile: Pope Pius XII and the Jews Rabbi David Dalin, Ph.D.

- Holy Cross' Pius XII and the Holocaust

- Anti-Pius

- Judging Pius XII from Christian Century by Kevin Madigan

| Preceded by Pius XI |

Pope 1939–1958

|

Succeeded by John XXIII |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |